When a building in Nairobi’s Huruma estate came tumbling down three weeks ago, killing more than 50 people, national and county government officials wasted no time identifying who the culprits were. On the morning following the collapse, President Uhuru Kenyatta, taking a break from preparations to set fire to the country’s ivory stockpile to tour the site of the Huruma tragedy, reportedly ordered the arrest of the owner of the building.

County officials were also quick to declare that the building had not been approved and was marked for demolition. The National Construction Authority also chimed in, declaring that another 57 buildings in the area had been found unfit for habitations. Demolitions of some of these resumed this week, after Nairobi Governor, Evans Kidero, suspended them for a week “to allow tenants to find alternative housing”.

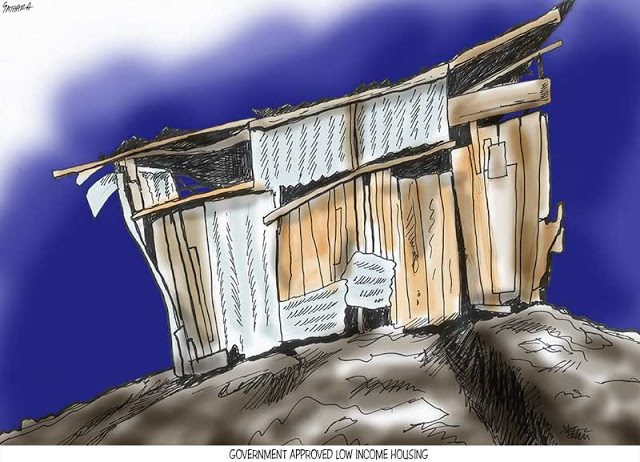

In all this, the problem identified by officialdom was clear: greedy rogue developers cashing in on the city’s acute housing shortage. They have been assailed for cutting safety corners to maximize profits, corrupting government officials and endangering thousands of innocent lives.

“Shortage of houses, poverty, greedy developers who do not obey the construction standards—construction without proper steel structures to support the building – and valuing money more than the lives are the major issues here,” says Nairobi county Planning and Housing Executive Christopher Khaemba.

Daniel Manduku, the CEO of the National Construction Authority, the body charged with regulation and coordination of the construction sector, says the country’s laws have not been sufficiently strengthened to deal with the developers. “The law has been weak. Developers are not forced or mandated to use professionals. That is why we’ve had very poor structures coming up over the years,” he says.

The scale of the problem does point to a collapse in building standards across the capital, perhaps even across the country. In January last year, the NCA warned that over 70% of residential buildings in Nairobi were unsafe.

However, in a piece penned in November 2014, Kwame Owino, CEO of the Institute for Economic Affairs, says that what is commonly seen as a housing problem what actually an income and employment problem. He says that in a country in which poverty is pervasive, “a cheap house will necessarily be a bad house.” He says the high costs of land and construction are squeezing the poor into ever more decrepit and unsafe housing.

“The largest cost component in construction is the cost of land and to use it efficiently developers build multiple storeys. The next largest cost is materials for pillars, including steel and mortar and this is where many developers cut corners, using substandard materials or even omitting the pillars entirely,” he adds.

Land prices in the city have grown exponentially over the last two decades and today rival, and sometimes even surpass prices for similar property in cities such as New York. A report released by property firm Hass Consult last year showed that real estate prices in the city had grown five-fold in the last seven years.

While many have attributed this growth to the rising demand for housing, the fact is that many of the current real estate projects do not target the poor, who compose the largest share of the under-housed in Nairobi. “Most of the private housing projects one sees are intended to house the middle and upper classes,” says Mr Owino.

In fact, even the middle classes are struggling to cope with the massive surge in prices. According to Mr Khaemba, they are being displaced and increasingly forced into housing that was created for low-income residents, which further reduces the housing available for the poor. “Estates like Umoja were previously meant for low income earners but the entire area has been taken over by middle income class,” he says. The fact that despite high prices, the country has less than 20,000 mortgages also raises doubts as to whether the demand for housing really explains the stratospheric prices.

A 2013 report by for Thomson Reuters Foundation by Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a Washington-based financial watchdog, gives a clue to what is really behind the stupendous ascent of Nairobi’s real estate. It shows that the amount of illicit money entering Kenya from faulty trade invoicing, crime, corruption and shady business activities has increased more than five-fold in a decade to equal roughly 8 percent of Kenya’s economy. According to the report, much of this money is laundered through the real estate and property market.

In effect, massive amounts of dirty money are being pumped into real estate, driving up prices and pushing the most vulnerable into crumbling housing. With the soaring land prices, as Mr Owino noted, a cheap house really is a bad house. And the fact is the vast majority of poor construction is in predominantly poor neighborhoods of the city, where people have low ceiling for rent. A study by design and engineering firm Questworks found that while the quality of construction work is poor across Nairobi, but was more alarming in less affluent parts such as Buru Buru and Eastleigh.

Even if implemented, the failed Jubilee manifesto promise to build 150,000 housing units and the county government’s promises to construct 14,000 units starting in June are unlikely to produce any lasting changes. They are likely to run into the very same problems that the Kenya Slum Upgrading Project (KENSUP), launched in 2003, has.

Its flagship project, dubbed “The Promised Land” by local residents, is a rise of multi-storied concrete apartment buildings behind Kibera. The apartments are heavily subsidized and have, for the most part, running water, sanitation and electricity. However, Kibera residents assigned houses or rooms (sometimes up to three families are allocated a single unit) have been trooping back to the slum, preferring the income that comes with sub-letting the units to a middle-class searching for affordable housing in a city with skyrocketing rents.

KENSUP Director, Mr Charles Sikuku, struggles to appreciate the irony of his goal as he told the Nation last year, to “move the slum residents from living below the poverty line to a Nairobi upper middle-class life,” without actually increasing incomes. Even worse, he appears blind to the fact that the real estate bubble is actually driving traffic in the opposite direction. His assertion that the poor are “ungrateful” for subsidized housing demonstrates a lack of understanding that he is housing real people, not just filling up buildings, and that these people will responding to the dynamics and incentives generated by a hyper-inflated real estate market.

In the end, housing is about people not buildings, a fact that appears lost to those charged with resolving the problem but who seem preoccupied with being seen to act rather than actually addressing root causes. Simply jailing developers and their corrupt accomplices, demolishing existing shoddily constructed buildings and enforcing building codes will not address the real problem – a critical shortage of decent, affordable rental housing for the poor driven by the ballooning land prices.

In fact, in the short term at least, some of them will worsen the situation. Enforcing building standards will come at a cost that already struggling tenants will be asked to shoulder, which will incentivize even more bending of the rules. Similarly, demolishing existing housing, as the county government is doing, will have the effect of driving up prices.

This has already been seen in Huruma where rental prices in the wake of the announced demolitions have reportedly gone up by nearly 50%. In such circumstances, the governments’ offer to pay rent for two months for the families displaced by the Huruma collapse (but not those the eviction orders will displace, or those whose rents will subsequently rise) amounts to little more than a band-aid on a mortal wound. Comprehensive solutions to this problem must therefore mitigate the immediate effects on the poor of enforcing existing laws and building codes. They must also look to policies that will increase, not reduce, the amount of decent housing available to them.

A walk around the supposedly middle-income neighbourhoods such Kileleshwa reveals the toll the distorted property market is taking. Numerous apartment buildings stand empty, their owners apparently unperturbed by the lack of tenants, even as property prices continue to climb.

As the dirty money pushes the middle classes towards the back, it is inevitable that they will take up whatever little decent space exists for the poor, squeezing them into ever more dangerous tenements. The truth is even government provided low income housing will do little to fix the problem if we do not take measures to enforce anti-money laundering laws and to pop the property bubble. If we do not, we should expect more Huruma-type tragedies.

This article first appeared on Gathara’s blog and has been reproduced with permission from the owner.